Written by Mercedes Acosta

With proper adherence to COVID-19 safety guidelines halting the physical convention circuit, many festivals have had to move entirely online. In the 2020 virtual imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival, the “Night of the Indigenous Devs” featured a live talk from five different Indigenous game developers and their works. In a spectacular show, we got to tune in for both solo and team-created efforts and hear these creative Natives talk about their work.

The sponsors, East Side Games, a Canadian games company known for its idle narrative games, tuned in first. #ESGCares is their charity effort that focuses on supporting marginalized people. Their current focuses are Women in Tech, LGBTQ+ issues, and Indigenous people. imagineNATIVE and Indigenous Game Devs offer a heartfelt thanks to East Side Games for their ongoing support.

The official show starts with a word from Beth LaPensée, maker of the Thunderbird Strike side-scroller and When Rivers Were Trails point’n’click adventure. Beth founded the Indigenous Game Devs network, which gives Indigenous game developers from all walks a space to showcase their work, chat, skillshare, and promote games.

Meagan Byrne, owner and lead game designer of Achimostawinan Games, spoke next. She had poignant words to say: “Too often are we told we have to present our Indigeneity in video games in a particular way.” Meagan talks about the value of a space where Indigenous game devs can come together and simply be, and be supported in the way they want to be seen.

After Meagan and Beth speak, we meet our first featured designer of the night. Shandiin Yazzie Woodward of Subliminal Games talks about Button City. From the gameplay, we get to view that it’s a wholesome, low-poly game focused on friendship and community. The central plot is about a fox and his friends trying to save an arcade in their town. The game looks sweet, and according to its creator, encompasses a lot of kid culture.

Though it features only animals as characters, there’s still a keen eye for representation; some of the show-cased game footage features a bunny character who is a wheelchair user. Shandiin mentions that her art background is almost entirely 2D—it affected her decision to use low-poly looks and a limited color palette that lend the entire game an appealing style. According to Shandiin, the modeling was both challenging and fun at the same time, and required thinking about breaking complex items into simple shapes. Button City is an adorable game that has light puzzling and endearing characters, and is a testament to what happens when Indigenous game devs are allowed to develop their own way, free of expectations.

Up next are Keara and Caeleigh Lighting, the Samson Cree duo who created Mîkiwâm. It’s a visual novel about people reclaiming gifts and connecting with ancestors in the face of colonization. Players can alter dialogue outcomes depending upon what tea they serve. Kaera and Caeleigh explain that they liked the idea of affecting outcomes and Indigenized this mechanic by using herbal teas. As the writer and designer, Keara was in charge of dialogue and tea choices. She speaks of the research she conducted on herbs.

Caeleigh, the artist, mentions the pressure on Indigenous artists to create things in a bubble of what’s “acceptable,” traditional—the two chose to fight back against this type-casting of Indigenous designers by setting Mîkiwâm in a fantasy alternate world. This way, there’s no pressure to tether themselves to specific places, peoples, and representations—an alternate fantasy world gave them freedom to explore with their imaginations. Both chuckle softly while speaking about their project—they wanted “good vibes” in this game. They wanted it to feel relaxing to play. One look at the calm and approachable artwork and muted palettes convinces players that they achieved that goal.

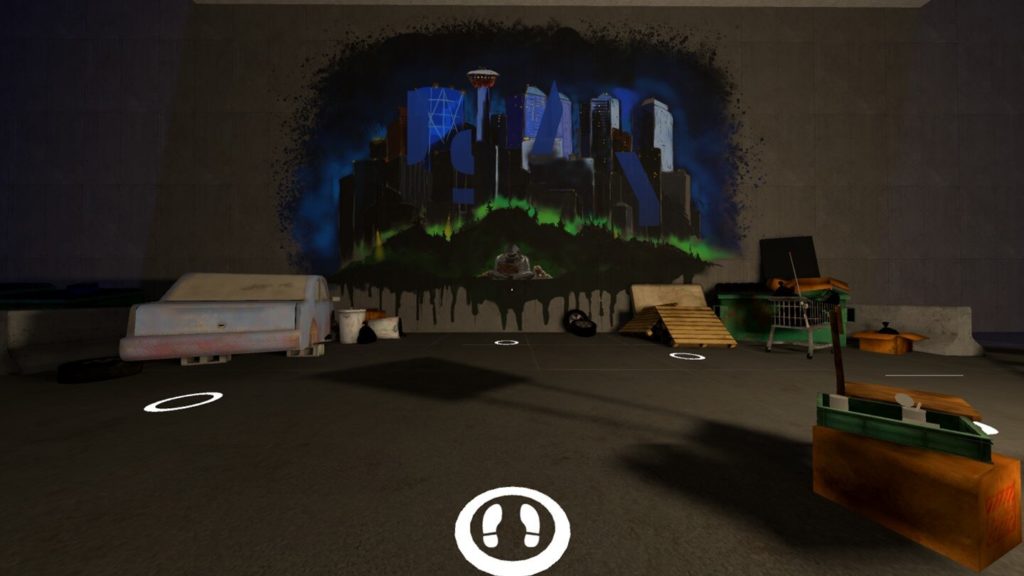

LeeAnne Ireland (Anishinaabe) of the Urban Society for Aboriginal Youth joins us next. She produced a virtual reality escape room in 2019 called Finding Victor with a group of youth and development by MAMMOTH XR. LeeAnne wanted to provide engaging ways to bring awareness to both youth and larger audiences on how to reach out for help and access resources. The VR game has players searching for their friend, Victor, who just lost his best friend to suicide. The player wakes to a phone call from a youth worker asking for help to find Victor, and players solve problems, complete puzzles, and find clues to trace Victor’s whereabouts.

The game is a work of love; heartbreaking legacies of intergenerational traumas are brought up, and the many causes of Native youth homelessness are explored. There’s a happy ending—Victor is found in a Youth Center, and the player sees him successfully transition to permanent housing. LeeAnne mentions the positive focus on urban, contemporary Indigenous art, including use of graffiti art and music. For many struggling Native youth who might not be as connected to their nations, it provides a modern element of culture.

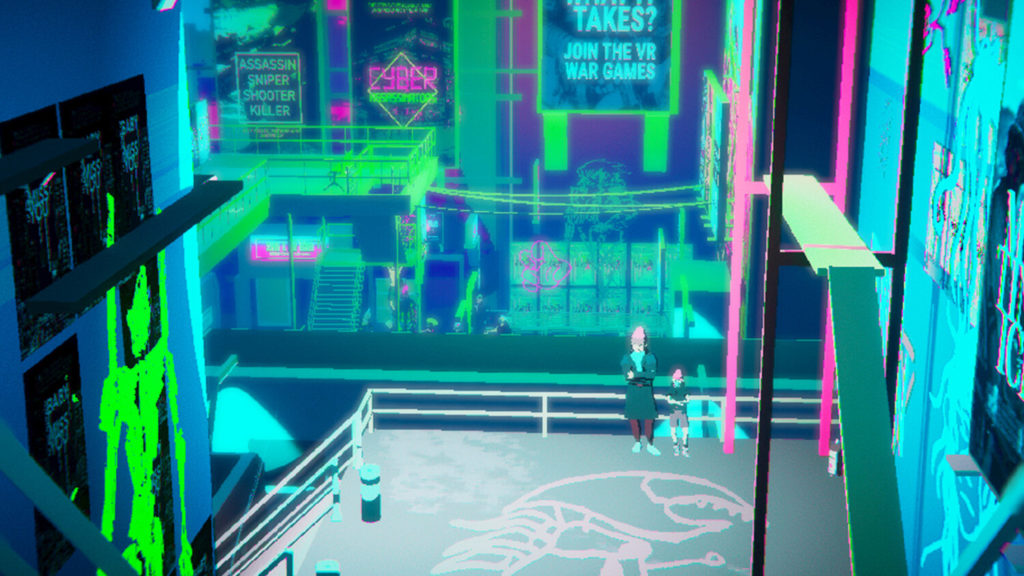

The fourth game dev was Christian “Chris” Miller of Silver Spook Games. A Native Hawaiian, Chris starts off talking about his dystopic cyberpunk game Neofeud. In his words, it’s about a cyborg caseworker, a sentient machine person, and a socialist princess taking on a cabal of neofeudal trillionaires who live in floating golden palaces above slums.

Chris transitions to discussing his experience growing up in poverty-stricken areas of Honolulu, but to some it sounds like he’s still talking about a dystopic nightmare. He mentions tiny, full houses with no air-conditioning and contaminated water; attending an elite private school in shabby clothes, because his father’s employment there granted him free tuition; living off Instant Ramen for days on end and crying over exorbitant medical bills. He compares this to the postcard-perfect side of Honolulu, owned by aristocratic white airline and hotel owners who carved up Hawai’i like medieval lords carving up fiefdoms.

These days, Chris has reached a wider audience and created a self-sustaining game company. He and his wife no longer live in abject poverty. But seeing art in the game (all done by Chris), and the stark conditions in which the second-class-citizen Machines in Neofeud live, it’s clear that Chris’s upbringing influenced the creation of Neofeud on a deeply personal level. His creative work speaks even more evocatively of his experience growing up alienated and Indigenous than his eloquent words.

Our final speaker of the night was Naphtali Faulkner, creator of Umurangi Generation. Naphtali is Ngāi Te Rangi Maori. He calls his game “many-layered.” It’s a first-person photography game that heavily explores Knowledge as an Indigenous focus, as well as deconstructs the Western gaze of oppressed Indigenous people and oppression tourism in general. Indigenous views of Knowledge as a living, existing thing around us features heavily in Umurangi Generation. It’s the emphasis for Naphtali as he talks about Respectful Design in a community sense and how he featured it in his game. Respectful Design, according to Naphtali, means a designer listens to the community and follows their directions before, for example, installing a well. “The designer’s job is to listen to them,” he says. He brought this into Umurangi Generation by allowing players to photograph what they wanted, how they wanted. The game doesn’t tell players if a photo is good or bad; the designer didn’t want to condition players to take photos a certain way, but rather allows them the option to photograph as they want. Player agency is important to Faulkner, just as community agency is important in Respectful Design.

The game, as mentioned, is many-layered—it confronts and evaluates neo-liberalism, poverty tourism, and Indigenous people as contemporary peoples. Modern existing Indigenous people are portrayed in contemporary clothing, and according to Naphtali, a mirror is held to the player to allow them an introspective reflection of their engagement with the setting and people, rather than allowing them a voyeuristic approach. It was key to portray Indigenous people as modern and contemporary; as Naphtali says of the Maori, “We’re not a static culture.”

The Night of the Indigenous Devs concluded with Meagan Byrne once again showing up to thank viewers and contributors, and with that, another round of Indigenous game devs are inspired to go and do their own things; in their own way, with their own space.

Missed the live premiere? The event recording will be available online starting Monday, October 26 at 7:00 p.m. EST through Achimostawinan Games at Night of the Indigenous Devs 2020.